A while back I started floating examples of poorly crafted script panels on twitter. I called it Comic Writing Crime and gave folks a chance to tweet back what they thought the problems were.

Thinking it’s a valuable exercise, I’m reproducing here in a bit more detail. Note, none of these are my panels (I make plenty of mistakes myself which I’m usually quick to point out), but these samples are pulled from actual scripts that come across my desk or onto my radar. Names and places have been changed to protect the innocent.

This will be an ongoing thing, so check back once in a while to see new crimes in action (and make sure you don’t commit them in your own writing!).

PAGE 1 – PANEL 1

A scene of the London skyline on a dark, rainy night.

What’s the crime?

Literally, that’s it. This is a classic example of a thin panel description (which you’re gonna see referenced a lot on this page).

Now I want you to think about a London skline… get an image in your head. Ignore the rain and night element for the moment.

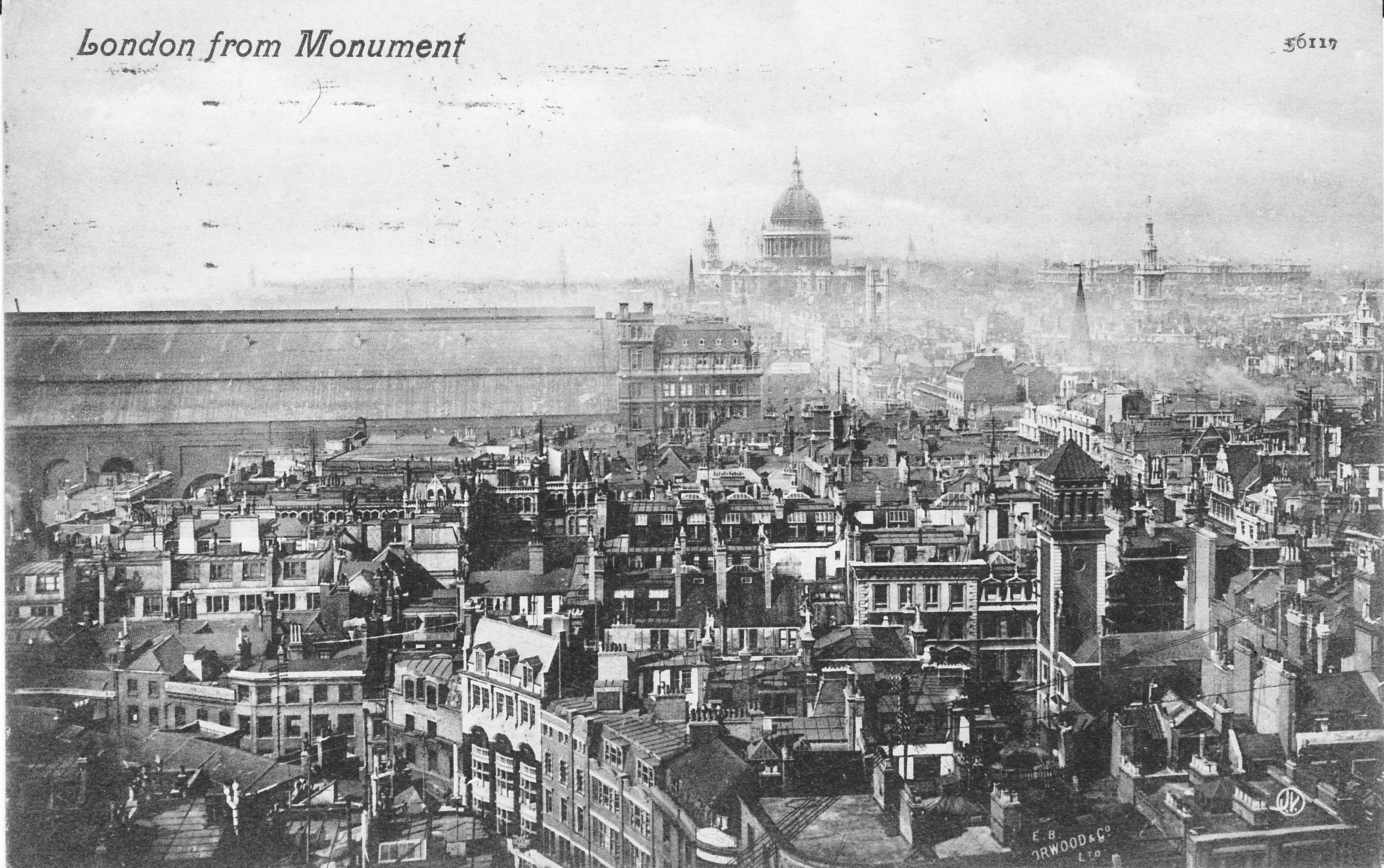

Now allow me to drop some images… have a look.

Here’s a London skyline. Is this what you imagined?

How bout this one?

This one?

Or this one?

Odds are without the iconic Big Ben, like this one, there’s a good chance you can’t recognize modern London.

Which brings up a really good point, the writer never specified CURRENT DAY London… so maybe this one works…

But since time wasn’t specified, maybe future London works?

Ok, so hopefully the demonstration clarifies why thin panels don’t work. Without a minimal level of description detail, you’re leaving the direction of the narrative completely open to interpretation. This creates a hit or miss atmosphere and promotes excessive project revisions.

Before we go on this one, let’s take a look at the only other details the writer gave us. Timeframe, night. Sound adequate? Hardly. Is it a full moon, half moon, no moon? Should the moon be present in the shot? Cloudy, clear?

The writer specified dark. But last time I checked nights are always dark (compared to day). So did he mean the sky is more dark, than most other nights (implying new moon)? Or maybe he meant, nobody has lights on in their apartments… Or maybe they’re saving electricity and turned off all the streetlights. Or maybe it’s a holiday and there are no cars on the road. There’s no way to know what “dark” means to this writer, because he didn’t explain it.

And lastly of course, rain. We all know what rain is, but I can give you a dozen types of rain. A fine mist, a light drizzle, a steady downpour, a thunderstorm, a monsoon, a spring shower, ok six, but I’m sure there are more.

To the amateur writer, these details may seem inconsequential. To the professional writer, these are all opportunities to define tone, mood, foreshadow, and otherwise establish the narrative.

Panel 4: Joe is getting up.

What’s the crime?

Another classic example of a thin panel description. Let’s pretend for a moment the writer already described Joe in detail. So the direction of this panel is: “is getting up.”

This direction is passive writing. If you’re gonna crash and burn with a meaningless thin panel description, at least put it in active voice, like…

Panel 4: Joe gets up.

So on its own, we of course have absolutely no idea what’s going on in this panel. We don’t know anything about the environment, what Joe is getting up from, what put him there etc.

The only time a really thin panel description like this is acceptable, is if the previous panels spent a lot of time establishing all those important elements. Sometimes this kind of panel can slip in during an action sequence.

If you just spent 5 panels showing Joe getting pummeled into the ground by a bunch of ninja, ok, the artist probably has his bearings for a simple Joe gets up… but not really.

A panel like this may not be wasted space in the comic (probably, but maybe not), the artist may inject enough life into it to work. But a panel description like this is ABSOLUTELY WASTED SPACE to the writer.

I mean that literally.

The writer had space to somehow (any-how) capture the narrative, and instead wasted it by giving a simple, minimal action. The writer did not even try to capture any of the 4 key elements to every comic panel (discussed at length in the Writer’s Guide):

Emotion,

Comictography,

Mise-En-Scéne,

and Movement (really capture the movement in descriptive visual writing).

I always tell folks, at the very minimum, get the emotional context of panel.

So in this example, even saying, “Joe gets up. His eyes scrunched in rage, the whites of his teeth flashing beneath a exaggerated snarl.” Capturing the emotion, at least gives a chance, the panel will have narrative heart.

Panel 3: Suddenly, it wakes up before the stunned eyes of 2 men. It howls 1 last time, before passing out.

What’s the crime?

This panel is not written visually. While that alone is crime, a far greater felony takes place. Let’s break it down.

- it wakes up.

- it howls.

- it passes out.

Three distinct actions… from one character… in one panel.

And technically, waking up, is one of those actions I discussed in the guide–a beat that takes more than one panel to establish. So really, the writer has this character doing 4 things in the panel.

Law #2 of comic writing, clearly states: A SINGLE MOMENT IN TIME, A SINGLE ACTION PER CHARACTER

Page Seven: Splash Page

Pull back several muddy footprints are apparent on the floor, and they exit out the open back door. Insert-David examines two white pills.

THE DOCTOR

DO THESE TELL YOU A STORY?

DAVID

AS A MATTER OF FACT, THEY’VE TOLD ME THAT JANE ISN’T MISSING. SHE’S ON THE RUN FROM A MURDER CHARGE.

What’s the crime?

Oh boy… ready for the list?

- Splash page is the first page of a book. Any full page art inside the book is “Full Page Art”. Technicality, so we’ll call it a misdemeanor.

- “Pull back several…” The writer of this script is clearly coming from a screenplay background. THIS IS SPARTA!!! I mean COMICS!!! Bring your knowledge of story telling, but leave your screenplay format (mostly) behind.

Coincidentally, STOP directing in your screenplays. Don’t tell the director to pull back, just explain what’s going on, let the director figure out how to shoot it. In comics, only add camera direction when it directly and is necessary to the narrative. - “Insert…” Insert in screenplay land is a way of calling for a cut to a close up of (usually) a static object/image. Since this guy is writing screenplay script and not comic script, I’ll mention that a lot of the time you don’t need to call for an insert, just cap the element you figure needs the insert. Again, just detail what’s happening and let the director direct:

… David empties a vial into his hand. TWO WHITE PILLS.

In comic land an insert is… wait for it… another comic panel. This writer is trying to call for full page art while including two panels of information. - Thin panel description. Split the description into its two separate panels and what information are you really given? “Somebody examines pills.” Really?

- Full page art for FOOTPRINTS !?!? Full page art pages are suppose to be pay-off pages. They bring a sense of intensity, shock, awe… Footprints leading out of an open door? Good lord, I’m afraid to read further. Is the climax someone answering their cell phone? Scene selection people. Numerous articles on here in that regard.

- Capping your dialogue. STOP THAT! It makes your letterer’s life more difficult.

- “…they’ve told me…” Passive writing. This is like a double passive whammy. (try to stay with me) Not only is the character relaying to the reader something told to him, but he’s doing it in past tense! “They have told me.” vs “They tell me.” So we don’t hear the clue telling him, we hear him, telling us the clue told him. UGH my head hurts. This distances the reader from the story about as much as you can.

Also, “Several muddy footprints are apparent”. Watch those ugly “be” verbs (am, are, is). You don’t need to tell us we’re seeing something… just tell us what’s in the panel. “Several muddy footprints cross the floor through the back door.”

Panel 1: Johnny walks through a sea of tightly parked cars in a west side NYC parking lot. Patricia waits in the foreground, holding open the door to the underground garage.

Patricia: What took you so long?

Panel 2: Two shot. Johnny looks nervous. Patricia looks annoyed. Both are passing through the door into the garage.

Johnny: Sorry, trains were late. So is the contact here yet?

Patricia: Not yet, should be here any minute.

What’s the crime?

Ignoring the fact that the panels are thin… This comic opens with what I call a continuity panel—basically opening too early, on something irrelevant. Since continuity panels should be killed, that’s violation number one.

Second, the scene is opening on a character entrance… again which should be killed in 99% of circumstances (unless the entrance has some specific relevancy to the story or character).

Though you haven’t read the whole script, I can assure you Johnny being late is in no way relevant to his character arc throughout the story, or the plot as it unfolds. Establishing Johnny’s entrance and him being late doesn’t evoke any relevant emotion or connection with the reader.

So the greatest violation of all, is that these two panels squander any opportunity to showcase something meaningful.

And this loss of opportunity almost always appears with these types of panels.

Even if the writer had infused the two panels with sharp dialogue filled with subtext… the panels would not be as effective had he started later, bypassing the entrances.

<Previous panels Monica is fighting with a mugger.>

Panel 4: Monica hits the man in his eye with the high heel of her shoe. It pops out, blood shoots everywhere.

What’s the crime?

This panel is so thin, it’s actually confusing… Did Monica jump up and high kick the mugger in the eye, or did she remove her shoe and wield it as a weapon? Not only would the former be reserved for a very special kind of lady… it would also have high comical or over-the-top campy potential. Which tone is the writer going for? Beats me he didn’t tell us.

Also, it’s clear the writer isn’t thinking visually in comic stills, but as one continuous action. Hitting the guy in the eye AND his eye popping out are two distinct beats. To capture the two together in one panel, it would be more accurate and efficient to say something like “Monica leaps into the air performing a Taekwondo high kick. Her stilleto heel gouges the mugger’s eye clear out of its socket, spraying profuse amounts of blood everywhere”

Panel 7: Monica in the back of the car, looks sad and inspects the broken, blood dripping heel of her shoe.

What’s the crime?

Again the thin nature of the panel–the lack of visual writing–leaves us uncertain… Is Monica looking down at her foot on the floorboard of the car? Or is she holding the shoe in her hand, examining it close up? I get the distinct feeling the writer doesn’t know the focal point of the panel (or the narrative moment).

And while we’re at it “looks sad” is an extremely weak verb-adjective combo. Is she genuinely upset, or sarcastically disappointed–is this another moment to inject humor? Accurately capturing the emotion can completely change the context of the panel.

Any time a panel conveys the wrong emotion it’s likely to clash with or muddle the dialogue.

Page 2-3: A text box tells us the location-Manhattan, NYC. A spread page of the a helicopter just landed on a pad on the lower east side waterfront. In the foreground FBI agent Cleo wearing a black suit and red tie walks from the chopper. A tactical vest his suit showcases a host of military gadgets, including a 9mm pistol. Next to him is another agent walks behind a man handcuffed in casual clothes. While Cleo walks proud and confident, the second agent and prisoner hunch over to avoid the choppers still spinning blades.

What’s the crime?

First, “a text box tells us” should be captured in the dialogue section of the panel as a caption;

Caption: Manhattan, NYC. Present day.

Second, the caption is a bit thin, especially for a double page spread. Is it night, day, busy, desolate. What’s the prisoner look like. Etc…

Lastly, while I can’t technically call it a crime, this spread is most likely wasted opportunity. Ignoring the fact that it’s an entrance… There is little of the four essential panel elements. Most notably, emotion. Generally you want to reserve full page art (and spreads) as climatic, emotionally charged moments. Or moments that turn the story really hard, injecting jarring narrative drive. Or, maybe, if your artist is out of this world talent, to simply capture a breathtaking scene.

But taking two pages, to say very little narratively, is wasted opportunity.

Panel 8: The camera pans out and goes above the shoulder of one of the combatants. Now we can see the fight is between a human cyborg that looks to be more machine than man and an insect humanoid creature that looks like a bizarre cross between a praying mantis and a cockroach. The creature stretches its body to swipe at the human with it’s large claws, but is blocked by an upswinging motion of the human’s sword.

What’s the crime?

First, besides being written passively, the real crime is in the opening line… “The camera PANS OUT and GOES above the shoulder.

Comics and live action screenplay writing are two different things (though you shouldn’t be adding that camera direction there either). You can not pan out in a single comic frame, and you can not move the camera twice in the same panel.

Once again, if you are going to include camera direction in your script, I’m a huge advocate of using screenplay style sluglines;

Panel 8:

EXT. ARENA – CRANE

A human cyborg that looks to be more machine than man and an insect humanoid creature that looks like a bizarre cross between a praying mantis and a cockroach, engage in mortal combat. The insect warrior stretches its body to swipe at the human with it’s large claws, but is blocked by an upswinging motion of the human’s sword.

That simple 3 word slugline is all you need to set the camera direction.

Second, I would give this panel a “F’ for visual writing. “more machine than man.” Like coffee maker machine, retro robot machine–with big gangly flexible appendages, futuristic machine with seamless shiny metal embedded with polished gemstones? The actual combat action described is minimal at best.

Third, there is no mention of one of the four KEY elements of every panel! Emotion. Is the human robot guy scared, angry, something else? And same for the insect, which circles back to visual writing–how do you show an angry mantis/roach man? I mean really, that sounds interesting to me.

Fourth, PANEL 8. Though technically not a crime, I’d bet a pancake breakfast it is. Even without seeing any other panels on the page. Why? Simple, it’s a big action panel specifically flagged as a WIDE (pan out) shot. So unless, the first 6 panels are tiny extreme close ups, which would be a rare sight indeed, it’s virtually assured this panel is cramped and losing impact.

Panel 6- A young redhead, age 25, dressed in a black t-shirt that has the Rolling Stones lips and tongue symbol on it and the sleeves ripped off and torn stone washed jeans gets into the van from the passenger side. She is also wearing a cowboy hat and knee-high leather boots. Her name is Grace, going by Gigi.

What’s the crime?

First, this writer didn’t read my article on introducing characters in panel descriptions. Shame, shame, shame.

Second, the only thing in this entire panel description that’t not character description is “gets into the van from the passenger side.” Good grief, we’ve got nothing going on here and no visual writing, heck no writing at all, to describe it.

Always assess the narrative weight of what you’re writing. As I’ve talked to elsewhere, character entrances and exits can almost always be cut. Why waste the space showing a character appearing out of thin air? Just cut to them appeared out of thin air and saying or doing something relevant!

The Grace/Gigi thing… Don’t do anything to complicate a character with dual names. Actually, I should write up a small specific article for this. I’ll do that now.

Panel 4- Looking past Jessica towards Mary, who has crossed to the door and now locks it. At the same time, from the shelves beside the door she takes an electric torch. Jessica watches her, drawn slightly out of herself by curiosity.

What’s the crime?

First, prime example of directing the camera when you shouldn’t. What does the opening “Looking past Jessica toward Mary” bring to the narrative? More importantly, it muddles the panel description big time. I think the writer is trying to call for an Over The Shoulder shot, but the direction just confuses and complicates the panel.

Notice the writer states looking past character 1 to character 2, then at the end, notes the expression of character 1. How exactly do you capture the expression of a character you’re looking past? Possible… impossible… confusing at best.

Next, who has crossed the door (past tense) and now locks it (present tense). Write in present tense. “Mary flips the lock on the left side of the door, sealing it tight.”

Third, apparently Mary is locking a door while at the same time taking an electric torch from the wall. Unless you’re Doc Ock, stick to one action per panel.

Lastly, comic script writers must write for clarity. “Jessica watches her, drawn slightly out of herself by curiosity.” Is the writer giving illustrative direction here, or implying something is attracting the character? And which character exactly is affected? When you end the first independent clause of a compound sentence on a pronoun, it’s easy to muddle the second part. And “drawn slightly out of herself by curiosity,” what exactly does this mean anyway?

If you have a confusing line like this and can’t reword it for clarity, unpack it–show it visually. “Intrigued by Mary’s actions, Jessica tilts her head and furrows her brow while bringing two fingers to her lower lip.”

Panel 2-: The local city police finally come on to the scene as Jane exclaims it’s all under control, soon cutting to her inside the detective’s office. The detective is reading off several charges as Jane slumps in the chair.

- Detective: … Speeding, unlicensed firearm, reckless endangerment!

- Detective: Need I go on Jane? I warned you last time, I wouldn’t be able to cover for you next time!

What’s the crime?

First, character dialogue in the description, not in the dialogue section. The inferred exclamation also seems in contradiction to the character’s actions at the end of the description.

Second, “soon cutting to her inside the detective’s office.” You can’t change locations in a single comic panel… sorry.

This is one of the reasons I advocate panel sluglines! Properly using panel sluglines increases efficiency and clarity tremendously.

Third, passive writing, “The detective IS reading…”

Fourth, let’s break down what this panel is telling us; 1) Police arrive. 2) Jane exclaims. 3) Detective reads Jane charges in his office. 4) Jane slumps in her chair. The panel is literally telling us nothing. How many police? Are they arriving with guns drawn in a panic, or eating doughnuts and singing Johnny Cash? Anything interesting with how the detective’s office looks? How bout the detectives emotional state as he reads? It says Jane slumps in her chair, but what’s the emotion/reason behind that slump? Being exhausted and being embarrassed are two entirely different slumps.

Fifth, excessive exclamation points. People don’t shout nearly as much as you think they do. The more you use something, the less impact it has, or in other words, save the shouting for when something really needs to be shouted.

Panel 4-: We see John in the computer room, sitting in a computer chair, fingering the air, interacting with the holographic system like a composer conducts an orchestra…

What’s the crime?

First, passive, “we see…”

Second and more importantly, this panel suggests movement which require multiple panels to convey. “interacting” and the analogy “like a composer conducts an orchestra”, both speak to movement. This shows a fundamental lack of understanding that comic panels capture a single moment in time.

Could an artist illustrate from this? Of course. But it would be far more accurate and efficient to speak to specific visuals, something like, “John touches a folder with his index finger on the holographic menu floating before him. The folder sits encircled by two glowing green rings.”

Panel 4-: … As we zoom in to the telephone screen, we begin the next part of the story.

What’s the crime?

Let’s ignore the passive and zooming and go straight to the second part of the descriptions; “we begin then next part of the story.”

Never tell the artist what you’re about to tell them. This is redundant. Double special cheeseburger don’t tell them what you’re about to tell them when it’s not even specific (like this example above). OBVIOUSLY the next part of the story is… well… next.

Tell them once, clearly and effectively the first time and that’s all they need to know.

But more to the point, don’t focus on telling the artist anything in your scripts.

Instead, show them the story unfolding.

You don’t need to say; “Telephone screen showing a large sum of money overdue, then begin the bank robbery scene.” Just write panel 1, telephone screen, yada, yada… then

Panel 2: Two guys with shotguns rush through a bank lobby, screaming at the top of their lungs…

Artists don’t need to be told what they’re looking at, they’re generally good at figuring that out themselves.

An exception to this rule is if you’re doing some sort of wacky scene sequences, a strange flashback, or other intercut of some kind, where the artist might not be clear which scene the material he is about to read belongs. In this case, it’s ok to tell the artist where they’re at (and one of the reasons I advocate scene sluglines in comic scripts).

Panel 6-: However many panels necessary to illustrate bob horrified over losing his bet on the Superbowl…

What’s the crime?

If you’re going to write loose and leave a panel breakdown up to the artist, if you know the description is going to require multiple panels to convey, don’t toss this to the artist on PANEL 6 (at the end of the page)!

6 panels is already a full (as in crowded) page. You’re creatively tying the artist’s hands and likely going to get a page that feels cramped.

Panel 6-: A butterfly flutters across the striking green leaves of the jungle. Separate small panels to show the movement of the butterfly. It lands on a tree branch next to an iguana.

What’s the crime?

I see this one often… A writer calling for additional comic panels, inside a comic panel. Trying to sneak it in as if a not calling a separate panel, “a panel,” makes it easier for the artist to illustrate and doesn’t count against the total page panel count.

BUZZZZ wrong answer.

Keep your panels separate and accounted for.

If you want to run a panel (or multiple panels) inside another panel, call it as an inset.

Panel 6: Exterior of a dense jungle. John, Joe and Jack backpack single file, sweating profusely.

Panel 7: Inset panel 6. A butterfly fluttering along.

Panel 8: Inset panel 6. A butterfly fluttering further along.

Panel 9: Inset panel 6. A long iguana tongue lashes out and snags the butterfly out of the air.

Panel 2-: Django throws the bowl of soup across the room with a deep scowl across his face. Small bits of bat meat and vegetables fly directly toward the camera. Bar patrons cower in the background. Django is allergic to bats and doesn’t eat it under any circumstances.

What’s the crime?

Last line, the explanation or motivation behind the character’s action. Motivations like this don’t add anything visually. The writer already said the character is throwing the soup out of anger, so what more does knowing he’s allergic add? Answer, nothing.

Not only do these superficial exposition dumps add nothing but bulk to the script, as information, they will almost always be immediately forgotten by the artist. The place for character details is a reference sheet or bible document, something the artist can jump back to quickly to find answers. Not buried like a needle in a haystack somewhere in the script.

Panel 5-: Still holding the bundle of fire sticks, Joro affectionately pats his mate and daughter on their backs. It’s important Joro’s skin doesn’t make direct contact with his mate or daughter, his hand, falls only to their animal fur clothing.

What’s the crime?

Always make sure the actions you describe are physically possible… Pat = “touch quickly and gently with the flat of the hand.” If anyone knows how you can pat two people at the same time while holding something in one hand, please let me know.

So the direction of action in this panel is either wrong, or requires more than one panel to express.

Hope you find these breakdowns helpful. More to come. ▪

About the Author —

Nick Macari is a full-time freelance story consultant, developmental editor and writer, working primarily in the independent gaming and comic markets. His first published comic appeared on shelves via Diamond in the late 90’s. Today you can find his comic work on comixology, amazon and in select stores around the U.S. Visit NickMacari.com for social media contacts and news on his latest releases.

I agree, kind of, with you on this but I think you still need to be able to give freedom to the artist in drawing the panels as well. I have come across so many scripts, especially from those that have ventured from television to comics, that are so precise that it leaves nothing for the artist to…well…be an artist. As an artist I would much rather a looser style of description per panel and allow me to be a storyteller, but the writer has to go in knowing this. If they go in with the thought that the artist is going to read each panel from their minds and not need exact descriptions, then you will be sorely disappointed.

Thanks for the comment Ben.

Absolutely, artists should have the freedom to add their own voice to the story. This is essential to getting a comic that’s greater than the individual contributions of each creator.

That said, an artist should never have to try to “figure out a panel”. The narrative should be clear. An artist should read a panel description, understand exactly what’s going on and decide from that starting point what creative decisions he needs to make.

Of course, some artists may prefer very loose scripts (like some prefer tight ones) and communication at the beginning of the project (if you know the artist attached to your script) is always the first step in making a great comic.

Write on, write often!