It’s a sad fact that in efforts to keep budgets down, editors are a part of the creative team often cut in indie comic productions (or hired in a limited capacity, usually just to proofread).

It’s a sadder fact that often, once I deliver a script to a client, that’s the last I see of it. I’m not always involved in a script’s full life cycle.

Comic scripts are all about communication.

Even on the best written script, questions, confusion, misunderstandings, misinterpretations and mistakes take place. The benefit your book receives from having someone dedicated to that communication can’t be emphasized enough.

You can often find me spouting on social media that “a good editor is worth their weight in gold.” They can (and usually do) have a tremendous impact on how the final book comes together.

Below are two showcases of how a good editor (or just keeping the writer involved) in production can make a difference in the final product.

I’m going to use two examples from my own work in Issue #4 of Convict Comics, Soul Mates.

Make no mistake here, I am NOT throwing anyone under the bus… especially, interior artist Claudia Balboni—she’s done a great job on the series and I‘d recommend her for any project. And as a young comic publisher, the following two examples are certainly within the realm of reason to slip by creator (turned editor for the series) Martin Chuzz. No editor catches everything. <Keep in mind, both of these talents are not native to NYC the setting for the story—in fact, both Claudia and Martin are not even from the U.S.—Italy and Australia respectively.>

The first example comes in the environment of a key scene in the book.

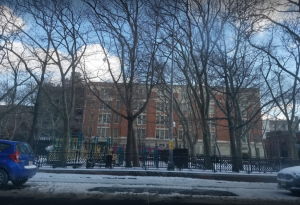

Notice in the first caption the script calls for “the Sara D. Roosevelt Park.” This is a very specific, real-world park in downtown Manhattan… (one I’ve stumbled through myself on more than one occasion.) Take a read and look.

Ok, so what’s wrong here? Well, to be honest, IF you’re not from NYC you probably don’t have a clue. Let me show you with a couple of pictures courtesy of google:

Yeah, so, the only park in Manhattan with trees anything like the panels in the page above, is Central Park. Certainly not Sara D. Roosevelt, which is totally urban. Now of course, this detail doesn’t alter the course or impact of the story BUT the series is otherwise grounded in authentic NYC atmosphere… kind of a love letter to city, and it does detract from the story, for anyone who knows NY.

Example 2, is a bit more specific.

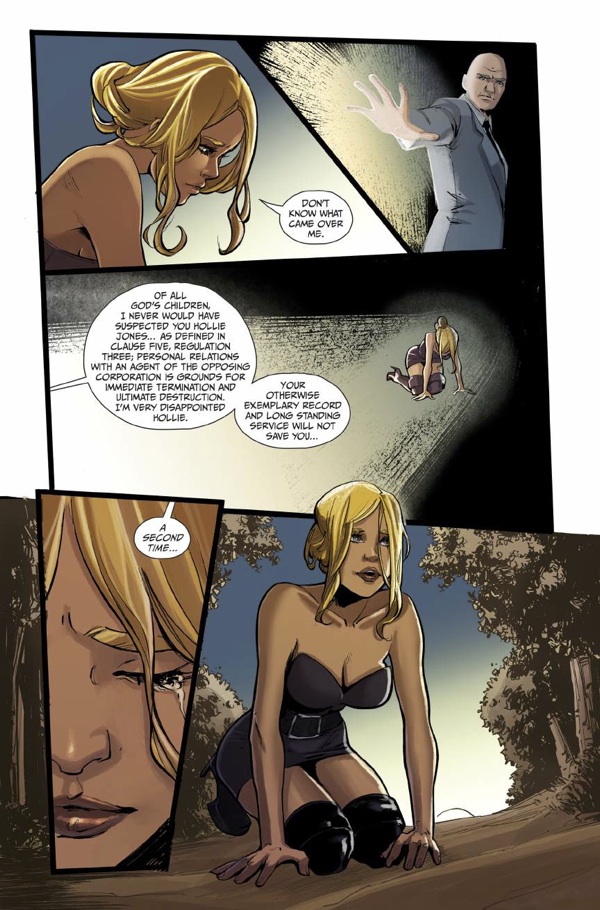

<It also showcases the relationship “tight” comic scripting has with the art.> First, let me show you two pages from the story. Read them and see if you can pick up on what’s going on, forget the backstory stuff, just try to follow in the moment…

- So here we have one of the main character’s Hollie getting beat down by a bunch of homeless demon folk.

- Archangel Michael, the bald guy, steps in and saves her with his demon nullifying holy light.

- At this point in the story, Hollie has broken some laws and Michael is inclined to kill her along with the demons.

Ok, so here’s the disconnect.

First, since the opening of the sequence, (the previous example), the entire setup takes place just before the break of dawn. The script called for everything to be set in that blue pre-dawn twilight color. This was captured a bit in the last panels of the first example, but, I would have pushed it home much harder in order to emphasize the end of the sequence.

Now the lighting is relevant, because the disconnect hinges on the last few frames where Michael turns his nullifying light on Hollie.

The idea of the script was that Michael raised his hand and shot out his light at Hollie. The reader sees Hollie consumed by the light thinking she is being killed, then the archangel delivers the line about a second chance, AND in the final frame we see the light is not Michael’s dangerous power, but the light of the sun at the start of a new day, as it rises above the penitent Hollie. (New day, second chance, see what I did there? ahhh, us goofy writers.)

I’m guessing by the art you didn’t pick up on that powerful, emotional transition.

Now I make no claims that my script was perfectly clear.

And the artist should always have the flexibility to change things up to tell the story “better”. But in this instance, I feel the essence of the storytelling moment was, not so much as broken, but lost… If I had seen thumbnails before going to final art, I definitely would have opened communication on the issue.

Don’t make the mistake of thinking these types of details are frivolous and this level of attention isn’t warranted.

Any detail in a comic you can fix with a little communication to make the book tighter, is a fix worth doing. Hopefully these two examples help illuminate the immensely underestimated value of a good editor (or writer who stays on with the book).▪

About the Author —

Nick Macari is a full-time freelance story consultant, developmental editor and writer, working primarily in the independent gaming and comic markets. His first published comic appeared on shelves via Diamond in the late 90’s. Today you can find his comic work on comixology, amazon and in select stores around the U.S. Visit NickMacari.com for social media contacts and news on his latest releases.