Grab a coffee, we’re gonna be here for a bit with this one. I was actually planning to put this on my paid member site, Story To Script, but decided I wanted to share it with everyone here on the free site.

You.

Make.

Me…

Promises Promises (knowing I’d believe)

I often talk about the critical importance of making (and keeping) promises to the reader.

It’s especially important at the beginning of the book, as the initial promises you make to the reader often dictate if the reader comes along for the ride, or puts the book back on the store shelf. (Nevermind the fact that our initial promises literally set the stage of everything to come.)

Anywho, our craft of writing is one-way communication. We talk to the reader, but they don’t get the luxury of talking back to us.

In the real-world, I might hand you a copy of Peerless and tell you straight-up, “Hey, man, check this book out, I think you’ll love it. It’s got tons of Kung Fu action, set in 70’s NYC during the blackout. If you like gritty gang fiction and Black Exploitation films, I promise you’ll love this!”

We might even have a conversation allowing me to reinforce and hype a bunch of promises of the book.

But as writer’s we don’t have the chance to personally hand our books to thousands of people…

Instead we make our promises in the narrative. And we do this by showcasing the things we promise.

Our presentation, is our promise.

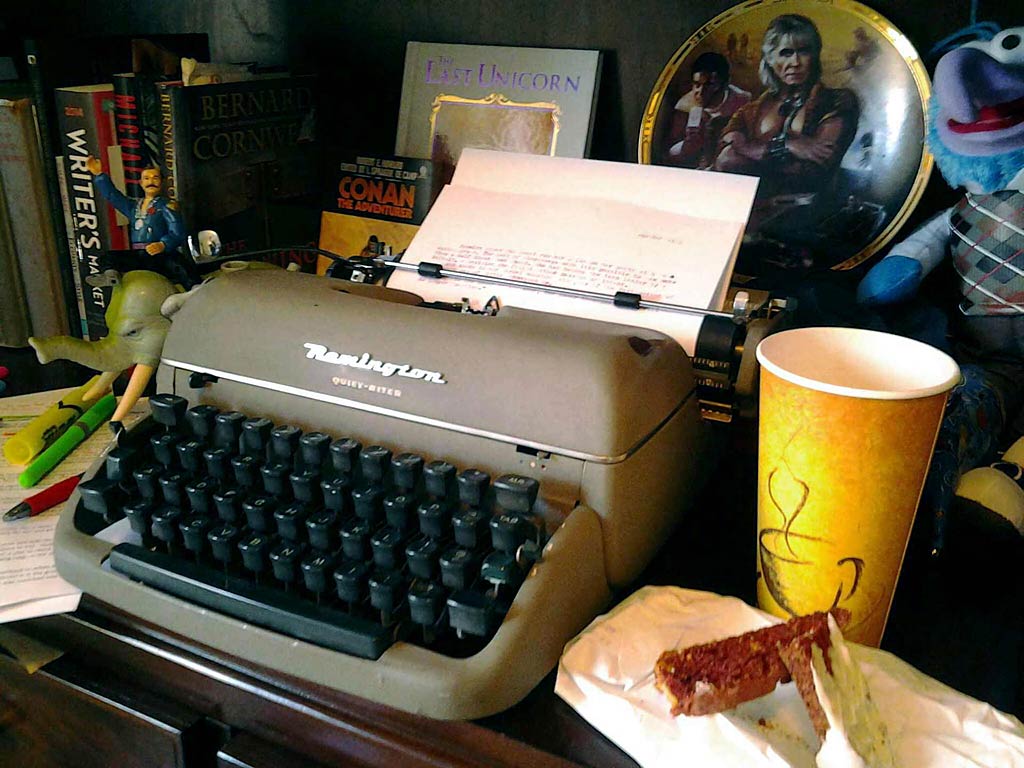

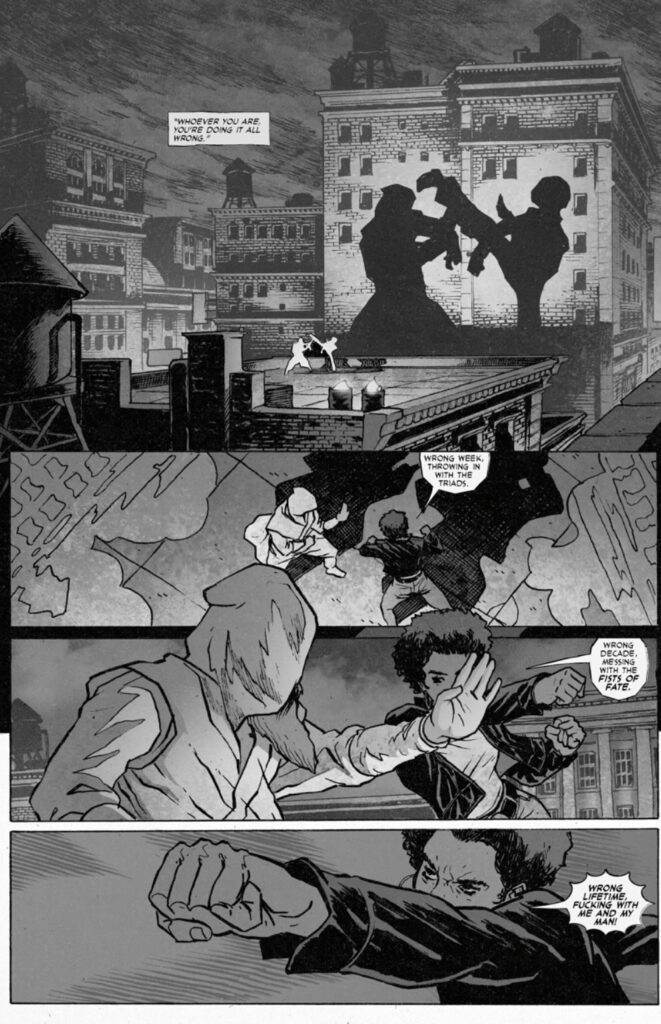

Let’s take a look at some of the promises I make on page one of Peerless. Normally, I would look at a full scene to assess the promises, as the scene is a more complete and coherent thought than a single page excerpt, but for the sake of space, we’re just going to run with the first page.

Three things jump out at me:

- A gritty urban environment. (It’s not defined on the first page yet, but the story is set in 1977 NYC).

- Kung Fu Action!

- A tough, trash-talking female lead.

Do you pick up on any other promises?

By far, the most common promises you make in your writer toolkit, will be the obvious ones. The ones you express clearly, openly and usually stay with for a significant amount of time.

Like everything I just listed above.

Though, sometimes, your promises may appear subtly or even completely in subtext. Subtle promises can work to enforce pacing, plot, or other narrative fundamentals, used primarily as a foreshadowing mechanic, to become far less subtle at a point later in the story.

Let’s jump right into another example, again, 1st page of The Man Who Died Twice:

Here I get:

- Cemetery = Dark and creepy. Death lingers. Possible gothic vibe.

- A period piece. (By their clothes and speech, I’m gonna say this is London somewhere around the beginning 20th century)

- Sherlock Holmes! He’s mentioned by name, so he’s somehow involved in the story.

- Crime! We’ve got some sort of mystery on our hands.

The first one in the Man Who Died Twice list, the cemetery, this one is a bit of a subtle promise. While visually, the cemetery is dominating the environment on this first page, the focus isn’t on the cemetery itself, but what’s happened within the cemetery. The promise of the cemetery is more in tone and in support of the main genre (more on that later).

Turning out attention back to Peerless, if the first scene opens on gritty urban, Kung Fu, from a trash-talking female lead… then the entire rest of the book was a modern medical drama, readers would seriously be like, WTF?!?!

In this example, our initial promises to the reader would be completely broken.

Of course, there are times when you may want to deliberately break a narrative promise… If we were actually working on a modern medical drama, and a Kung-Fu gritty urban trash-talking female lead had some clever tie in or symbolism or whatever, to the actual story. But breaking promises is the exception to the rule, and a topic for another time.

If we read page one of The Man Who Died Twice and the rest of the story was a sci-fi space opera… I mean, shit, I don’t even know how you could connect those two off the top of my head. That would just throw readers for a bad loop.

Remember, the majority of people buying your book are NOT going to buy your book completely cold. They’re going to look for something. Anything, to get an impression and insight into the story. Some folks may be easy sells, only wanting one or two things, of which might be pretty broad in scope. Other folks might be hard sells, they may demand a bunch of things, or want things explained in detail.

So what we present, what we choose to focus on as writers, becomes the very things we promise the reader will see more of.

Narratively developing focal points and directing the reader, is key in making promises.

In Peerless, we can see a water tower on the rooftop. In TMWDT, in the last frames of page 1, that’s a shovel handle sticking out of the dirt. Just because something exists in the background, doesn’t mean we’ve promised something around it.

In visual mediums, just noticing something can be dismissed as part of the Mise-en-scene. But taking note of something, that creates a promise.

I assure you, Peerless is NOT about urban water towers…

HOWEVER, if perhaps someone important drowned in a water tower in the story, then I might actually decide to focus on the water tower for a few panels (or possibly pages). Of course, water towers by themselves aren’t much in the promise department “Hey look at all these sexy water towers! Can’t wait to see more of those babies later on…” So as a pretty unattractive plot element on its own, I’d have to fall back on the danger they represent or otherwise come up with creative and engaging ways to stay on water towers.

Perhaps a random kid playing on the rooftops almost falls into one, or during a fight, one character punches through the old rotted boards of one, flooding the fight with tons of water.

This is why we say, your opening scene needs to hit effective and accurately on the core aspects of your story. Because the core aspects are generally the biggest selling points of your story.

Take note:

What we begin, (open or promise, narratively speaking), becomes the cause.

The development and conclusion of those things, becomes the effect.

Cause and effect are an inescapable dynamic of writing. (To try and write without them, is to venture into the avant-garde.)

In turn, we can further recognize:

Every good scene supports an existing promise, or creates a new one.

GOLD STAR to you if you realized, this is the essence of narrative drive.

Or in other words, if you write a scene that neither supports an existing promise OR creates a new one, you’re creating a scene with no narrative drive.

Chekhov’s gun

If you’re reading this article, you most certainly already know about Chekhov’s gun principle; that every element in a story must be necessary and any irrelevant elements should be cut. If a gun appears in the story, somebody better shoot it.

Ultimately what Checkov’s gun alludes to is “Always keep your promises!”

If you glimpse a gun on a wall display, among some background material, this is neither here nor there… BUT, If you introduce a gun. If you take the time to narratively make the gun a focal point, you’ve just created the promise, that someone at some point, will use it.

If you break your promises (deliberately without justification, or unintentionally), you’re breaking the fundamental cause and effect of the writing.

Breaking your narrative promises is a sure way to confuse and muddle a story. But even more so, it’s likely to disappoint your readers, coming across anti-climatic (because the climax of the original promise is literally never resolved), and ultimately just deliver an unsatisfactory experience. In a worst case scenario, broken promises will outright piss your readers off.

MYSTERY

Wait, wha-wha-what!??

Man, every time, there’s that one guy…

Alright, alright, Mystery is the one genre, where unreliable narrators and otherwise completely manipulating the promises at hand are par for the course. Although we can argue, even in the mystery genre, the core promises remain intact, but beyond those, the whole idea of mystery relies on the ability to sort of obfuscate the REAL promises of the story, allowing the reader to SOLVE and DISCOVER the real promises of the narrative.

With a clear understanding of promises and their relevancy, we can now look into GENRE itself and illuminate a few other helpful points.

Remember, Genre itself is all about EXPECTATIONS.

What you expect as a writer is necessary to include in the story and expectations of the readers before they even open your book.

Over the years, as genres have solidified themselves, some promises have become engrained in us. Although good stories strive to manifest these promises in unique, new ways, it’s hard to consider a story an authentic genre work if it doesn’t have these familiar promises within.

Genre Rules

![]() Before we continue with the promises, it’s worth noting here that if you want to write GOOD genre fiction, you need to follow the genre’s rules. Though ‘principles’ are perhaps a more accurate moniker; a fundamental way of looking at the genre that helps you decide what conventions and obligatory scenes to choose and how to effectively use them.

Before we continue with the promises, it’s worth noting here that if you want to write GOOD genre fiction, you need to follow the genre’s rules. Though ‘principles’ are perhaps a more accurate moniker; a fundamental way of looking at the genre that helps you decide what conventions and obligatory scenes to choose and how to effectively use them.

If you’re finding this article useful, you can support everything I do here, while supporting yourself, by jumping over to Story to Script and grabbing my genre guide pdf for $11.99. This guide compiles all the genre articles I’ve written to date over at Story to Script. It covers the rules to Drama, Horror, Thrillers and Action. The cover is shite, but I promise you the content is far beyond the price of admission!

While most writers would assume these fundamental genre rules define a work as in or out of genre, we’ll see in a moment why this isn’t really true.

OK, back to the promises of genre, which come at us as:

Genre Conventions

You can think of genre conventions as more abstract or broader promises.

- A bunch of Kung Fu fights in a Kung Fu comic is a convention (or broad promise).

- Pupil and Master relationships in a Kung Fu comics are conventions (or broad promises).

- Fighting school honor is a classic Kung Fu convention. (or broad promise).

Obligatory Scenes

Where a genre convention gives you broad direction to work from, more specific promises manifest in more specific scenes. This further you move into a subgenre, the narrower the promises become.

- A training scene that captures an increase in skill, technique, and power is a common obligatory scene (or specific promise) in kung fu stories.

- A showdown between gunfighters is an obligatory scene (or specific promise) in a western.

- A first victim, who is taunted before being brutally murdered by a hand-held weapon, usually a blade of some kind, is an obligatory scene (or specific promise) of a slasher story.

Assessing Genre

Interestingly if you google ‘how to determine genre of your story,’ you get a million articles talking about genre itself… but none of them attempt to make any physical benchmark in actual scope of the work.

In other words, nobody says “if you write a 90,000 word novel, at least 50,000 words need to be horror, to be considered horror.”

It’s really strange to me that nobody discusses this.

This ambiguous approach gives way for streaming services to slap a million genres on every movie they stream… “Hey that scene in the coming-of-age flick was scary, ok, let’s add horror to its genre list!”

But more to our point, if you wrote a 90,000 word novel, and put all the hallmarks of the horror genre in one 2,000 word chapter, should that be considered a horror story?

No, says I.

I’m in the boat that in order for a work to be considered a specific genre, that genre has to carry forward for a significant portion of the work. Genre is actually more about the volume of material that stays in genre, than the individual points themselves.

So you write a 90,000 word novel that somehow doesn’t hit on any of the horror conventions, or obligatory scenes, yet, stays in genre the entire time… guess what, you just wrote a horror novel… though probably a shitty one.

Whether your wield conventions and obligatory scenes effective separates GOOD genre fiction from BAD… it doesn’t separate genre fiction from non-genre fiction.

In vs. Out of Genre

Looking back to Peerless, a bunch of kung fu action is clearly a promise of Action/Violence, which speaks directly to its main genre.

So anytime I write a scene that hits directly on action, OR in some way supports the action, I’m writing in genre.

Anytime I write a scene that doesn’t hit directly on action OR support action in some way, I’m writing out of genre… or more accurately, I’m most likely writing in a different genre.

It’s important to be aware of when you’re writing in and out of genre, as I see it and say, genre isn’t defined by the individual parts alone, BUT in the volume of material and relationship between the parts.

Novice writers who don’t pay any attention to writing in or out of genre, usually struggle to define their genre later on… or just pull the genre labels out of their arse, for whatever they’re hoping it reads as…

But if you actually take the time and pay attention, the story itself, will tell you exactly what genre(s) it is.

Let’s take a quick look at page 3 of Peerless:

This is personal, emotional scene of the main character reading a letter. Looked at for what it is, this scene has nothing to do with Action. It’s not even supporting action in any sense of the word.

This scene is strictly DRAMATIC.

So if this scene stretched for say 4 pages, then I had a bar scene where the characters drink and talk, which hey! just happens to be in the book, and that scene runs for 4 pages, those 2 scenes alone would total 8 pages of drama driven material, out of 24 total pages in the book…

or 33% of the issue.

Personally, I have a hard time assigning a genre label to any work that doesn’t at least stay in-genre 25% of the time.

In this case, Drama makes the cut in Peerless issue 1, making the story an Action Drama!

Note that if the 4 page bar scene later in the book supported action, if the scene was a bar brawl or if the characters were testing their weapons in preparation for a big fight in a later scene… those scenes would be in genre. Reducing our drama to only 4 pages total, or 16% of the issue.

When a genre drops below 25% in a narrative but still remains present, it’s more accurate to say the story has “undertones” or “elements of” said genre.

Just another quick example of the 25% rule in action.

If you have a 90 page fantasy screenplay and 9 pages (9 minutes of a 90 minute movie) fall in the horror genre. 10% just doesn’t define the whole vibe of the movie… whereas, 25% or 23 pages/23 minutes, while not overwhelmingly horror, that’s a solid chunk of the story experience.

Labeling your Scenes

As you gain experience writing, especially if you stick with a specific genre, you won’t likely need to keep a running list of which scenes are in what genre. You’ll be able to slap the labels on the fly.

I can think back off the top of my head to novels I’ve written years ago and still have an idea of which chapters were in what genres. Writer brain for the win.

But when you’re less experienced, or just really want to keep track, there’s nothing wrong with jotting down the genre to each and every scene. If you follow my comic scripting template, you could even pop it in under the scene declarations. Perfect spot for em.

Keep in mind, a scene can represent multiple genres. A monster chasing the protagonists, for example, would likely be Horror and Action. Also, each genre gets it’s own assessment of up to 100% penetration in the story. If your story contains parts of every genre there is, each part together does NOT need to combine for 100%.

A’ight, I decided to go back and take note, Peerless breaks down as follows;

Scene 1 – 2 pages – Action

Scene 2 – 2 pages – Drama

Scene 3- 3 pages – Action/Comedy

Scene 4- 2 pages – Drama/Comedy

Scene 5 – 6 pages – Action

Scene 6 – 4 pages – Drama

Scene 7 – 5 pages – Action

16 pages Action / 8 pages Drama / 5 Pages Comedy or 66% Action / 33% Drama / 20% Comedy

This means, Peerless issue #1, is in fact, an Action – Drama story, with comedy undertones.

As a side note, if you want to be anal in your genre assessment, you can apply the same 25% rule to each scene or page even. Meaning if there’s a 1 panel gag in an action scene of of 4 pages (20 panels), there’s really no need to assign a comedy label to it. For the Peerless breakdown above, I just ballparked it based on my impression of each scene.

Obviously, highest penetration in any genre should be listed first, so clearly, Peerless is first and foremost an Action story. The drama bit means it’s got humanity and heart baked into the cake.

Expectations, Promises, Rules, Conventions, Obligatory Scenes all coalesce to form Genre. A familiar, but hopefully new experience that covers and comforts you like a warm blanket on a snowy winter day. Be a reliable writer and always keep your promises and your fans will thank you for it. ▪

About the Author —

If you enjoy this article, please share the direct link on your social media.

Newcomer or veteran writer, if you’re working on a project that needs commercial success, Nick urges to you read this intro article.

Nick Macari is a full-time freelance story consultant, developmental editor and writer, working primarily in the independent gaming and comic markets. His first published comic appeared on shelves via Diamond in the late 90’s. Today you can find his comic work on comixology, Amazon, and in select stores around the U.S.