I reckon the most common use of SFX in comics, is using them as their name implies, to accompany a thing making a sound. (I’m going to throw in some panel examples from Vertigo’s Mad Max Fury Road.) I often refer to this as;

On The Nose SFX

Though this gives vibrancy, depth and engages the reader by tapping (or at least attempting to trick them into tapping) more than one sense, use On The Nose SFX sparingly. Used in limited amounts, these SFX not only catch the elements I just mentioned, but they add additional overall emphasis to the panel in which they appear.

As a general rule of thumb, if the panel you’re about to add an On the Nose SFX to isn’t the most important panel on the page, try to use another sound elsewhere.

You get far more mileage out of a SFX in your script, if you give it more specific purpose—make them work for a living (after all, you gave them the privilege to be in your book!)

Tone & Mood SFX

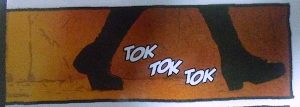

The next most common use of SFX comes into play when you script a SFX to compliment or enhance the tone, style, mood or overall feel of the narrative.

While this panel is technically also an On the Nose SFX, the noise in the panel clearly comes from the shoes in walking in the panel, the writer isn’t likely adding the sound so you know what shoes against cement sound like… he’s adding it to create mood.

Sounds of this nature have subtextual and possibly symbolic meaning.

In this instance, the feet echoing in the hall announce Furiosa’s first appearance. An appearance the writer dramatically extends over a handful of panels. To me, this ‘tok tok tok walking’ enforces her lone wolf, rogue warrior opposition to the rest of Immortan Joe’s gang.

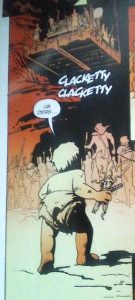

Movement and Action

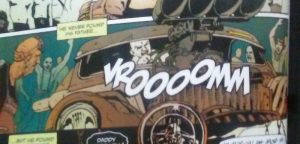

A more impactful use of SFX is applying them to images that capture movement or action that is not clearly revealed in the art.

Remove the SFX from the left image, and the moving platform suddenly loses all sense of motion. It simply becomes a platform hanging in the air.

Similarly, remove the SFX from the War Boy revving the car’s engine, and you’ve got a War Boy grabbing onto a steering wheel–it’s actually almost comical without the SFX.

In both these instances the SFX directly supports and enhances the narrative of the panel.

Before we go any further, 2 points;

1. Synchresis:

This is a fancy movie production word that revolves around what we see and hear, or more accurately the relationship between those two things. Expectations and psycology play big factors in what sounds present, with what images and the meaning of those relationships.

In some ways, Synchresis is almost like character archetypes for sound.

Here’s how it works, look back at the Furiosa walking panel above, but instead of tok tok tok, what do you get if we replace it with;

“Smiff Smiff Smiff”

I would be confused, because my brain doesn’t connect that with anything.

In contrast, what if it had,

“Squish Squish Squish”

I’d think her shoes were wet or maybe the ground was soft.

“Clang Clang Clang”

She must be rocking some metal armor boots or maybe walking on a tin floor.

You get the picture.

Synchresis is an important concept to understand. When you grasp it, you allow yourself to place more potent SFX. Sounds that aren’t necessarily real-world accurate to the visual, but psychologically more effective.

When using a SFX ask yourself, what sound can you use that will most effectively express the meaning or feeling you wish to express. As long as it doesn’t contradict the visual (or mental expectation), thinking outside the box, can be a real boost here.

2. Noisy Pages:

No matter how you deliver your SFX, the other thing to keep in mind is the overall sound of the entire page. As a general rule, I like to think of this as volume. One SFX, even a big explosion, isn’t that loud, but when every panel starts spitting out SFX, it’s like standing in a marsh with a flock of flamingos.

Noisy, abrasive and if nothing else, distracting.

Now sometimes in some intense action scenes or such, you may want really noisy pages. Just be aware every time you start loading pages up with SFX.

Lastly, and perhaps most importantly,

Direct Narrative Support SFX

The most impactful SFX are the ones that clue the reader directly into the narrative itself. The emphasis not on the sound itself, but the role or purpose of the sound relative to the story.

Picture a panel of an abandoned wasteland city with the SFX, “VRRRRRRRRR”

Second panel, a girl running in a panic, more “VRRRRR” “They’re coming!”

9 out of 10 readers just realized this dystopic story is about to open with a mutant motorcycle gang.

And that tenth dude who didn’t figure it, he still figured something potently horrible is approaching. The SFX isn’t just representing a sound, or even setting the mood/tone, it’s actively participating in the story, enforcing or building one or more fundamental narrative elements, in this case, jeopardy and tension.

Second example, let’s think aliens.

Ripley and Hicks move through the sewer chambers of the atmosphere processing station. Hicks’s tracker keying off the approaching aliens, “Beep… …Beep… … Beep… Beep… Beep… Beep… Beep. Beep. Beep. ” “Ripley, we’ve got to move… NOW.”

It’s not about “beep beep” it’s about what “beep beep” means in the story.

Ok, you’re probably thinking these two examples mostly show the same story elements… mostly…

Let’s take my Cyberpunk novel, Crashing Eden this time. Yeah, it’s not a comic, but the scene works to illustrate the point.

The protagonist wakes up at one point disoriented in a strange penthouse. He’s had a bad drift into the virtual network and his head is throbbing in massive amounts of pain. He’s also got blood all over his hands, but we won’t get into all the details. Carr (that’s the hero) hears an annoying high-pitched noise, which he comments on a few time, thinking it’s just feedback from his neural implant. As the scene plays out and a corpse appears, Carr realizes the sound is real–a tripped security alarm–announcing the crime scenes he’s inadvertently stumbled into.

Based on what I just described, can you think of any ways to use SFX to directly support the narrative shaping up there?

If you can get more of those in your scripts, you’ll be aces. The more your SFX work, the more effective you pages and narrative will be. Easy as eatin’ pancakes. ▪

About the Author —

Nick Macari is a full-time freelance story consultant, developmental editor and writer, working primarily in the independent gaming and comic markets. His first published comic appeared on shelves via Diamond in the late 90’s. Today you can find his comic work on comixology, amazon and in select stores around the U.S. Visit NickMacari.com for social media contacts and news on his latest releases.